An Enquiry into Violence

by Jordan Cunningham (PhD candidate in English Language and Literature/Letter)

Introduction

This article argues that violence is never justifiable, regardless of the cause, and explores this through the lens of normative ethics. The inquiry extends to considering the permissibility of resorting to violence in service of a cause and discerning the criteria by which some causes are deemed just while others are not. This perspective will be applied to the contemporary issues surrounding immigration and the widespread civil unrest witnessed across the United Kingdom. I posit that violence should be avoided when multiple alternative approaches are available. While asserting one’s rights via peaceful means is justifiable, resorting to violence contradicts the principles of rational discourse and leads to loss for all parties involved.

With this in mind, we should highlight strategies to avoid violence. For instance, the critical discourse around violence should recognise the inherent link between literature’s ability to illuminate societal issues and how much it can achieve actual change. It is important to note that while literature can highlight these issues, it is not a solution. Often, a perception of elitism within the discourse oversimplifies the issue and fails to investigate the underlying causes of hatred. I introduce a theoretical framework that integrates literature with a historical-psychological methodology to examine violence through the lens of socioeconomic disparities. Using the philosophical model of normative ethics, I advocate for analysing historical and contemporary instances of hate and violence within their real-world contexts and recognising that the influence and interconnectedness of literature and history are significant. To understand this, we must look at the recent scholarship and what it reveals about how violence is being studied.

Literature review

The critical discussion of violence in its many forms is wide-ranging but can be characterised into three subgroups.

Religious violence

Chouraqui thoroughly examines the concept of “religious violence” (Chouraqui 2021, 21) and its profound implications. The analysis underscores the intricate nature of religious violence, emphasising that its association is not intrinsic to religion but rather linked to the formulation of obligations (Chouraqui 2021, 21). Chouraqui scrutinises the ongoing discourse concerning religious violence, encompassing its correlation with secular modernity, initiatives for prevention, and meta-ethical considerations. Additionally, it delves into the phenomenology of duty and its role in perpetuating violence, particularly mass violence (Chouraqui 2021, 21).

Chouraqui analyses the connection between religious violence and specific justifications, as well as the defining characteristics of religious violence, such as generalisability and immoderation. The assertion is made that religious violence is set apart by its universal purpose and lack of regard for context (Chouraqui 2021, 21). The primary argument in the essay that links deontological ethics to extreme forms of violence is rooted in the concept of “phenomenological necessity” (Chouraqui 2021, 35). Chouraqui contends that excluding context from the realm of justification, a characteristic of deontological ethics, results in a phenomenological necessity associated with extreme and extensive forms of violence (Chouraqui 2021, 35). The nature of deontological ethics, which prioritises duty over contextual considerations, may lead to situations in which violence is perceived as the sole plausible resolution (Chouraqui 2021, 35). Chouraqui posits that this correlation is not merely coincidental but an inevitable consequence of duty implementation, distinguishing it from other ethical frameworks. I agree with many of Chouraqui’s insights; however, his main contention is flawed. Context is always present and evident in some way or another. The violence may seem mindless, but the reasons why people do the things they do always have contextual explanations.

Racial Violence

In contrast to religious violence, Petteway analyses the prevailing methodologies in epidemiological research on racial disparities within the United States. It sheds light on the power dynamics and injustices inherent in knowledge production, underscoring the marginalised status of community knowledge and the predominance of white scholars (Petteway 2023, 6). Petteway asserts that we must address the structural racism and colonialist underpinnings of the research enterprise. Petteway advocates for the transformative use of poetry to counter the epistemic types of violence that spread across large portions of populations and groups, such as in instances of racial hatred (Petteway 2023, 7).

This approach employs poetry as a vehicle for knowledge production and expression. It aims to centre marginalised voices and present counter-narratives to the detrimental impact of epidemiology (Petteway 2023, 8). Poetry is a strategy for healing which challenges established scientific discourse and promotes discourse on the representation of diverse perspectives. My assessment of this approach is that it constitutes an elitist proposition. While poetry and literature may yield positive effects, it is presumptuous that individuals entrenched in poverty and adversity will alter their perspectives because of poetry. Often, people in these situations have little access to books and no need for them when being able to feed and clothe their families is their main struggle. Literature is more valuable for viewing people’s situations rather than as solutions to the situation.

Further to Petteway’s analysis, Lawrence and Hylton study Critical Race Theory (CRT), which has evolved from academic circles into mainstream discourse and focuses on racialised experiences in Western social democracies (Lawrence and Hylton 2022, 256). It emerged in the mid-1970s as a response to the inadequacies of critical theory regarding race, aiming to address systemic racism (Lawrence and Hylton 2022, 257). Broadly, CRT posits that racism is pervasive and operates through systems of white supremacy and emphasises the importance of including black and marginalised voices in scholarship (Lawrence and Hylton 2022, 258). The aim is to challenge the neutrality of research, highlighting the need for methodologies that address racialised power dynamics and advocating for a more critical perspective (Lawrence and Hylton 2022, 260).

Lawrence and Hylton advocate for incorporating language studies into the development of race theory, theorising that racism is perpetuated through language systems (Lawrence and Hylton 2022, 261). They assert that a crucial area of focus lies in examining racial hierarchies and their cultural implications as conveyed through language (Lawrence and Hylton 2022, 261). This perspective gives rise to Critical Race Semiotics (CRS). CRS seeks to scrutinise visual culture, emphasising the harm of racial representations in society (Lawrence and Hylton 2022, 261). By understanding these impacts, we can effect change. Rejecting the notion of fixed racial categories, CRS promotes a flexible understanding of racialisation and its interplay with other social identities. Critical Race Theory (CRT) promotes research that directly caters to community needs, advocating for the fusion of scholarly work and social justice (Lawrence and Hylton 2022, 262). CRT underscores the need for sustained engagement and contemplation of racial justice in contemporary culture.

Political Violence

Tongeren discusses violence and language politically, stating that: “actions speak louder than words” (Tongeren 2023, 17). Tongeren further states that: “[philosophers] work with words’ and therefore the theme of violence, we probably feel a greater sense of powerlessness than we do when discussing other themes” (Tongeren, 2023, p. 17). Tongeren distinguishes two types of violence within political violence. Firstly, one is “characterised by absurdity and irrationality [which] conflicts with reality so we cannot comprehend it” (Tongeren 2023, 17-18). Secondly, quoting Verhoeven, violence is “something that we… think about…but [also] something that we are against and thus think against” (Tongeren 2023, 18). Tongeren validly observes that “[t]he aim of violence in its pure form is to silence and objectify the other” (Tongeren 2023, 20). Tongeren states that:

violence can only exist for humans, who are the only creatures to have language and logos. Although like ourselves animals are also subjected to what we call the violence of nature, they do not comprehend this as such. This is because, as far as we know, man is the only creature to contemplate the meaning of life, to seek its sense or significance, for which purpose it needs language. However, violence is a senseless phenomenon, and in that sense it is ‘dumb’. It is not so much that senseless violence is a particular category of violence, but rather that senselessness is a defining characteristic of violence’ (Tongeren 2023, 24).

Tongeren’s analysis presents valuable insights but has a significant flaw. Many disenfranchised individuals assert that actions carry more weight than words, as they resort to violence when they perceive no alternative means of expression. Their perception stems from feeling unheard, leading them to employ physical means to convey their message. Additionally, philosophers, in their exploration, engage not only with words but also with human actions, at times verbal and at times otherwise. Language constitutes an integral facet of the human organism and race; hence, the discourse concerning language embraces the entirety of humanity.

Moreover, violence is not devoid of rationality, as socioeconomic factors significantly contribute to incendiary behaviours. Tongeren’s view generalises the worlds in which many different people live, where daily violence is a stark reality. The prevalence of irrationality serves as a daily reality for many. Humans are influenced by language, but people are also bodily beings; as much as language, our bodies influence us and our decisions. The primal urge for destruction and the impulse to break through our daily existence drives many in the acts they commit. Finally, I cannot entirely agree with the term “senseless violence”; there is no such thing as “senseless violence”. Comprehension and contextual drives are always present in violent acts. A primal and thoughtless crime has stemmed from a prior cause enabling “senseless” acts. Further, it is contradictory in that Tongeren says humans are the only creatures capable of language and logos, of being able to attribute violence to a concept, to an end product, as it were. However, violence is also “senseless”. This is, in my view, not true.

Considering these three types of violence, we find that the prevailing body of critical literature exaggerates the significance of language while diminishing the role of environmental and contextual factors. While both aspects hold importance, it is imperative to strike a more equitable balance that acknowledges the applicability of literary and linguistic analyses to real-life societal challenges, particularly those involving hate and violence. An aura of elitism arises when individuals who lack firsthand experience with poverty or economic hardship endeavour to expound upon matters beyond their complete comprehension. While this in no way justifies hate and violence, it is evident that denigration alone does not offer a solution. Understanding an issue is a prerequisite for its effective mitigation. A more profound comprehension of the catalysts perpetuating entrenched prejudicial perspectives, particularly concerning class and economic disparity, can be attained by employing a theoretical model that integrates literature with a historical-psychological methodology. The deployment of the normative ethics philosophical model accentuates this issue by meticulously examining historical and current instances of hate and violence within real-world contexts. It is not simply a question of literature or history in isolation but rather the conjoined influence and interplay of the two. To understand this, we need a mode to highlight their interconnectedness supplied by normative ethics.

Methodology

It must be stated from the start that the immigration issue is inherently multifaceted, with varied impacts on individuals. I recognise the limitations in fully comprehending the experiences and challenges of others, whether they are rooted in economic disparities or a sense of neglect by their homeland. While acknowledging the fundamental right to express dissenting viewpoints, it is essential to exercise discretion, as expressions inciting hatred and violence are self-defeating. As a guiding principle, normative ethics is a critical lens through which permissible actions and avoiding violence are contemplated, ensuring our decisions are informed and thoughtful.

With this in mind, normative ethics states: “[there] is one and only one factor that has any intrinsic moral significance in determining the status of an act; the goodness of that act’s consequences” (Kagan 1998, 70). From this, normative ethics argues that “morally forbidden” (Kagan 1998, 71) acts are prohibited even if they serve a moral good. Many who support a normative ethics perspective highlight examples where a great evil is committed for the collective good. Kagan uses the example of five patients needing a specific organ to survive. One patient has all the organs needed for the others to survive. Therefore, is it morally justifiable to sacrifice this one patient for the benefit of the other four? Kagan states that this is incompatible with normative ethics because of the need for violence and harm to achieve its aims (Kagan 1998, 72).

One scholar whose research looks into ways to define acts as morally good or bad is Taylor, whose area of focus is Normative Case Studies (NCS), which serve as empirical instruments for examining normative philosophical inquiries and addressing tangible societal issues and educational disparities (Taylor 2024, 302). NCS differentiates itself from philosophical thought experiments and qualitative case studies by its empirical grounding and emphasis on normative examinations (Taylor 2024, 305). Taylor observes a current trend in philosophy towards greater engagement with empirical realities through case studies. NCS works by straddling the domains between fictionalisation and abstract philosophical inquiry as they engage with realistic social contexts alongside intricate normative inquiries (Taylor 2024, 307). NCS represent a form of empirically engaged philosophy that integrates both practical and theoretical dimensions, enriching normative analysis (Taylor 2024, 310).

Utilising my theoretical model derived from normative ethics, we can contextualise the underlying causes of persistent violence across diverse cultures and historical eras. To exemplify this, I will provide some background literary and historical examples and then select a textual piece, William Faulkner’s ‘Dry September’ (1931), to demonstrate this. This selection underscores the crucial role of literature in providing insights into normative ethics and societal issues, as literature reflects and critiques societal norms, albeit without necessarily providing a definitive resolution. Normative ethics will be used to evaluate historical and contemporary examples of violence to highlight their commonalities. Historically, violence has consistently failed to achieve its aim, and as in the past, violence has failed, so will it fail in the present and future. Using normative ethics in my analysis will draw out the evidence for this contention through textual and historical examples to exemplify how the values of normative ethics are frequently ignored.

Analysis

Before beginning my textual study into normative ethics, we must collate some background information on how violence has historically been understood. Throughout history, the use of violence as a basis for moral judgment has consistently failed. Machiavelli, in The Prince (1532), advocated for ruthlessness, stating that in the absence of a higher authority, the end result should be the primary consideration:

in the actions of all men…one must consider the final result…let a prince conquer…and his methods will always be judged honourable and praised by all’ (Machiavelli and Bondanella 2005, 62).

This implies that a leader should be praised for employing violent methods to maintain power. This attitude justifies the committing of violence for the right cause. However, this belief in the necessity of relentlessly pursuing power has led to prolonged suffering for humanity. History, with its numerous examples, has shown that violent regimes collapse. Even those with good intentions, initially aiming for liberty and equality, descend into reigns of terror. This historical evidence is crucial in understanding the futility of such methods.

In connection with this, Jahnke et al. studied the causes of political violence in young individuals. The study delved into the influence of depression, empathy, aggression, and identification with political violence (Jahnke et al. 2022, 113). The findings indicated that personal, push, and pull factors influence political violence outcomes (Jahnke et al. 2022, 114). Push factors, encompassing political dissatisfaction, personal discrimination, trauma, humiliation, and group deprivation, may propel individuals toward violent acts when exposed to ideologies and social networks advocating violence to achieve political objectives (Jahnke et al. 2022, 120). Pull factors play a significant role in motivating participation in political violence and pursuing social acceptance that is not readily available in their daily lives (Jahnke et al. 2022, 121). Lastly, personal factors such as empathy, depression, and aggression highlight the underlying issues experienced by many who join violent causes. This suggests that societal support inadequately addresses their concerns, leading them to seek alternative means of addressing their challenges (Jahnke et al. 2022, 122).

The identification and understanding of psychological risk factors associated with political violence outcomes among adolescents and young adults are crucial for comprehending the underlying psychological factors for political violence. Jahnke et al. delineate three primary psychological factors. Firstly, a deficiency in empathy or diminished empathic concern may heighten the probability of participating in politically violent acts (Jahnke et al. 2022, 123). Secondly, depression is correlated with an increased risk of engaging in politically violent conduct (Jahnke et al., 2022, p. 124). Lastly, propensities towards aggressive behaviour increase the propensity to partake in politically violent acts (Jahnke et al. 2022, 125-126). Comprehending these psychological risk factors is imperative for formulating impactful prevention and intervention strategies. These strategies, once implemented, hold the potential to significantly reduce the risk of political violence among adolescents and young adults.

If we examine this issue from a UK-specific standpoint, it becomes evident that resorting to violence is an unsound foundation for instigating change. A pertinent illustration is the 1958 Notting Hill race riots, during which individuals from the impoverished white working class engaged in acts of rioting against perceived Caribbean migrant threats, who they felt jeopardised their economic opportunities. Although rooted in misinformed beliefs, the decision to employ violence failed to serve the interests of the white working class; on the contrary, it exacerbated the situation. The violence resulted in the imprisonment of nine rioters and aggravated racial tensions, leading to subsequent eruptions of violence. Violence perpetuates further violence in an unending cycle. In contrast, historical figures exemplified by Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. have demonstrated that non-violent resistance yields notable achievements, albeit not flawless, but with superior outcomes and heightened emancipation for the oppressed. What is needed is a more direct approach to the issue that deals with the underlying issues which contribute to violent and extremist behaviours.

Dire circumstances often prompt individuals who are economically disadvantaged to seek a target for their frustrations. However, these individuals find it challenging to identify a tangible entity to hold accountable, as governments and their departments tend to be impersonal and distant. Individuals who voice their concerns about their methods within disadvantaged communities are also susceptible to social exclusion. To draw out how literature with a historical basis can aid in understanding this issue, I will refer to an excerpt from William Faulkner’s ‘Dry September’ to elaborate on this perspective and show how a normative ethic framework can be discerned from the story.

‘Dry September’

Normative ethics stresses the need never to allow violence to guide your decisions. Even if you think you may be right, violence is never the way to achieve justice; this is doubly true when dealing with speculation, speculation that ignites widespread hatred. In Faulkner’s fiction, impoverished and marginalised whites are depicted as trapped in a world of white anxieties that skew their perception of blackness as a means of compensating for their ongoing oppression. They exist in a realm where they invent and project their fears onto African Americans. This distorted projection of white fear is exemplified in Faulkner’s short story ‘Dry September’, which is the story of a rumour. It is alleged that an African American man named Will Mayes has sexually assaulted Miss Minnie Cooper, a white woman. This rumour is being discussed in a barbershop where the proprietor of the barbershop, Hawkshaw, and the other customers discuss the rumour, with Hawkshaw being the only person present to doubt the rumour, the rest of the men prefer to “take a white woman’s word before a nigger’s” (Faulkner 1951, 161). Eventually, another man named John McLendon enters the barbershop and rouses the rest of the men to come with him to hunt down Will In a lynch mob led by McLendon, a man with deep-seated issues in his personal life. The story concludes with the lynch mob kidnapping Will to lynch him, whilst Hawkshaw takes no part but significantly cowers and hides. Hawkshaw is the only character who attempts to question the validity of Minnie’s claim and tries to dissuade a lynch mob from forming to hunt Will.

In ‘Dry September’, the ideology behind bigotry and hate is exemplified by McLendon, who strives to assert his importance to Jefferson’s society by upholding the normative ethics of his society. As he enters the barbershop, it is highlighted that “[h]e had commanded troops at the front in France and had been decorated for valor” (Faulkner 1951, 160). What he does in Jefferson is not stated, but it can be assumed that his role is less noble than in the war. He enlists his men in the barbershop to undertake a mission that he feels is vital for maintaining the moral code of his society. Whether Will is guilty or not is of no consequence; McLendon wants a reason to maintain white power and his power as a paragon of white virtue over African Americans. McLendon wants to go back in time and be a commander again, upholding the customs of Jefferson and the traditions of the South he has been ingrained to believe in since birth, which are his only recourse to achieving this. To relive his prior importance in the war in his present circumstances. McLendon’s leadership of the mob in ‘Dry September’ is his only route to achieving this. Therefore, he must transcend normative and moral boundaries to remain significant.

Faulkner’s works explore the “white mind”, unearthing its innermost struggles in reconciling a tumultuous past. In Faulkner’s fiction, poor and disenfranchised whites are shown to be stuck in a world of white fears which distort blackness as a form of compensation for their own continued oppression. Such a phenomenon can be understood as psychological projection, whereby white anxieties are projected onto the black community. This distortion of reality perpetuates harmful stereotypes and reinforces systemic oppression. Faulkner’s works explore themes related to racism and prejudice by incorporating literary techniques alongside horrific real-life events such as acts of racial violence like lynching and torture. These real-life events are more terrifying than anything literature could conjure up. Through this approach, Faulkner’s works expose the evils of racist thinking and prejudicial attitudes. They invent their fears and cause them to become a reality to themselves when they are nothing more than mere fantasy. What is shown as the true horror is what these fears cause whites to do to others so they can exorcise the ghosts in their heads. For whites, the horror is only real psychologically because they invented it.

What will be highlighted is the distorting force that either destroys individuality or allows a person to avoid their responsibility when perpetrating evil. Faulkner depicts the absurdity of white men, such as the tradition of upholding racist values and societal views on white women’s purity. The story portrays the loss of individuality in the lynch mob and how nameless citizens, who are not unique in any way, are capable of the cruellest acts. The fiction details horrific events like lynching and racist violence and Faulkner’s representation of them to portray the reality of life in the US for African Americans at the time. However, the insidiousness of the “white mind” is pronounced where many of their fears are psychological and self-imposed, creating a warped worldview.

One explicit example of this issue is McLendon, who projects onto his life his racist fantasy in terms of protecting Southern women from an imaginary, yet to McLendon real, threat of predatory African American males. McLendon lives in a gothic world, which he views in romantic terms but is anything but that to others, and he becomes a villain whose villainy stems from his fears of anything non-white. Faulkner studies white identity as it is influenced by the predominant social circumstances of the story’s locale. The white Southern male, when presented with a situation that challenges his society’s codes and ethics in terms of protecting Southern women from predatory African American males, alongside the opportunity such a situation presents for the white Southern male to project their insecurities onto another, serves as a lethal combination.

When we consider this in terms of normative ethics, we see that hatred distorts rational thinking skills. Despite there being no evidence as to the crime having taken place, hatred overrides any consideration of morality; they feel that committing a moral evil like murder is preferable to allowing their worldview to be challenged. Normative ethics can then help reveal two tenets of bigotry. Firstly, the perpetrators of violence often are afraid of what they will be without their whites, and they commit violence in the name of this as it is all they have to cling onto, hence why they are so murderous in maintaining it. The story presents marginalised whites as being imprisoned in a world of white anxieties. These anxieties pervert blackness to excuse the continued subjugation of them. This creates a psychological projection in which white fears are transferred to blacks. This kind of factual distortion feeds damaging preconceptions and keeps systematic oppression alive. The white male characters in ‘Dry September’ feel powerless in their everyday lives, but the chance to victimise others weaker than themselves gives them a chance to regain power. All attempts to dissuade the mob are disregarded. They do not care if Will is innocent because he is an African American, and society has taught men like McLendon to expect African Americans to act this way. If Will has not committed the crime, it does not matter because he is an example to all African Americans of the white man’s power. The story begins thus:

the rumor, the story, whatever it was. Something about Miss Minnie Cooper and a Negro…

“Except it wasn’t Will Mayes,” a barber said…” I know Will Mayes. He’s a good nigger. And I know Miss Minnie Cooper, too”…

“Believe, hell!”…”Wont you take a white woman’s word before a nigger’s?”

“I dont believe Will Mayes did it,” the barber said. “I know Will Mayes.”

“Maybe you know who did it, then. Maybe you already got him out of town, you damn niggerlover.” (Faulkner 1951, 158-159).

From the beginning, it is reported as a rumour, unconfirmed and pure speculation, which the barber emphasises. However, the youth insults the barber for taking Will’s side and questions his loyalty to his race for even questioning a white woman compared to an African American male. This insult carries over to questioning Hawkshaw’s Southernness. A white man who defends an African American is not a Southerner, and their identity is called into question for even suggesting Will may be innocent. At the beginning of the story, many different white men are present in the barbershop, and the rumour is discussed for its validity. No one suggests a lynch mob; for all its racially charged discourse, violence is not immediately present. As the scene progresses, McLendon starts discussing violence and convinces two other men in the barbershop to join him in hunting down Will:

The screen door crashed open…His name was McLendon. “Well,” he said, “are you going to sit there and let a black son rape a white woman on the streets of Jefferson?”

Butch sprang up again…” That’s what I been telling them! That’s what I–”

“Did it really happen?” a third said…

McLendon whirled on the third speaker. “Happen? What the hell difference does it make? Are you going to let the black sons get away with it until one really does it?”…

“Find out the facts first, boys. I know Willy Mayes. It wasn’t him…

“You mean to tell me,” McLendon said, “that you’d take a nigger’s word before a white woman’s? Why, you damn niggerloving” (Faulkner 1951, 160-161).

McLendon enlists the members of the mob by appealing to their Southernness, their code to uphold the purity of the white woman from a black menace, illustrating their masculinity to do anything for the South and its values. Wyatt-Brown outlines these Southern values in three essential “Southern honor” (Wyatt-Brown 2007, 14) components. The first is “self-worth” (Wyatt-Brown 2007, 14), which, if successful, gives the Southern male a sense of his part in society and that he is an influential member who contributes. The second component is “the claim before the public of that self-assessment” (Wyatt-Brown 2007, 14) that the Southern male expresses this view and ensures all those in his society recognise their value. The third component is “the assessment of the claim by the public” (Wyatt-Brown 2007, 14), which is that the Southern males’ claims are accepted by his community and his prestige is assured. All three components show that the Southern male craves acceptance and power. Failing to achieve this aim led to deep “shame and guilt” (Wyatt-Brown 2007, 155). Psychologically and societally, the Southern man would become an outcast from himself and from Southern society who would question his value. This perspective leads to men needing to assert their value at any cost, and therefore, normative ethics is discarded in favour of an artificial set of values.

From a contemporary viewpoint, Wyatt-Brown’s tenets apply to all societies, such as the one in the UK during the riots, where a supposed enemy to the “white British” way of life is threatening to overtake the nation. This challenges people, predominantly men, to step up, as it were, to defend their homeland. This demonstrates their worth to the nation, which they feel has often forgotten about them. If you come from a low-income working-class family and you dare to step out of place, you also risk becoming conflated with the “other”; you become the enemy yourself. Likewise, in Faulkner’s story, being on Will’s side threatens to place that person in the same bracket as Will, outside the norms of society and at risk of violence if they persist in supporting an outsider. This fear led to joining the mob or remaining silent about their true thoughts: “[another] rose and moved toward him. The remainder sat uncomfortable, not looking at one another, then one by one they rose and joined him” (Faulkner 1951, 161). The only person who leaves the barbershop with the compulsion to stop the event is Hawkshaw:

The barber went swiftly up the street…When he overtook them McLendon and three others were getting into a car parked in an alley…”Changed your mind, did you?” he said. “Damn good thing; by God, tomorrow when this town hears about how you talked tonight-“…

“Will Mayes never done it, boys,” the barber said…

…

They stood a moment longer, then they ran forward… “Kill him, kill the son,” a voice whispered. McLendon flung them back.

“Not here,” he said. “Get him into the car.” “Kill him kill the black son!”…The barber had waited beside the car. He could feel himself sweating and he knew he was going to be sick at the stomach (Faulkner 1951, 164-166).

After this moment, Hawkshaw jumps from the car to escape his situation. Hawkshaw, in some sense, is a part of the spectacle, but unlike most whites, he is disgusted by racial violence, yet he is not confident enough that he can stop it. He cannot bear to participate in the lynch mobs’ activities, yet Hawkshaw realises the danger he has placed himself in by exiting the car and not participating. Realising this, he hides in a ditch to avoid the car returning from murdering Will: “he left the road and crouched again in the weeds until they passed” (Faulkner 1951, 168). Hawkshaw is exposed, and the story ends. We never see how society would treat him after the story’s end, but it is safe to assume his standing in the community is damaged. This situation also bars them from living in reality; they must try to pretend to themselves and others that what they know is wrong is right. Therefore, this could imply that some whites in the story who voice racial prejudice may not feel this way themselves. However, people like McLendon and Southern society pressurise these people to conform and take part.

Because of the powerlessness they feel, poor whites project their anxieties onto the black community. This often stems from the economic positions many find themselves in. From Faulkner’s story’s perspective, this powerlessness stemmed from the end of the US Civil War and the fear of the crumbling of the plantation system and the switch to sharecropping by landowners. Godden draws attention to “tenant slavery” (Godden 1995, 24), which encompassed whites and blacks. However, whites were blind to how African Americans could be an ally in the fight against white oppression of the poor. The “white mind” cannot see beyond race, and it remains strong enough in the “white psyche” to avoid the possibility of working alongside African Americans. Instead, it leads to more hate as they feel threatened for their jobs by blacks because they share some similarities in that owning class whites control them both.

Therefore, this system marginalised poor whites. Debt peonage in the sharecropping system had, in the mind of whites, made them equal to the African Americans, who still only just recently had been their inferiors; therefore, they became violent and attacked what they felt erased their whiteness. The Southern-owning class benefited from poor Southern whites reacting against African Americans as it aided them in maintaining white superiority over African Americans and superiority over the poor whites who were fighting their battle for them. The white tenant was enslaved to the labour market, which perpetuated poor white poverty because it gave them employment, which was all they had (Godden 1995, 25). Therefore, preying upon white fears allowed the system to remain. If African Americans were attempting to steal jobs, this would mean death for poor whites. Therefore, the poor white’s “virtual slavery” (Godden 1995, 26) persists in an endless cycle of hate. Whites saw black sharecropping families competing with their families, which precipitated the problem.

Godden highlights a pertinent point that white tenants were “not slaves, but nor were they free” (Godden 1995, 27). The white tenant occupies a surreal middle ground where they are part of a pure “white race” who rule over others. Nevertheless, they are poor and under the rule of an owning class who use them like they use African Americans. Therefore, doubt creeps in about whether they are any different from African Americans. It is this that scares poor whites and causes a crisis in their sense of racial superiority. Any groups or persons who can offer comfort from this fear are welcomed; this helps explain the prominence and success of hate groups like the KKK as they could prey on this fear. If you remove African Americans from the equation, the problem should disappear. Poor whites will have more opportunities, and blacks will be enslaved once again. Work was the only way for poor whites to gain back their autonomy and humanity now that African Americans were emancipated and were human rather than commodities.

Godden highlights how the owning class is not unburdened in this situation: “neither owners nor labourers were “free’’ (Godden 1995, 30). All are tied to a racist capitalist system which persists and traps all within a system which oppresses all and causes whites to continually oppress others whilst killing their inner humanity and strengthening their fears. The Gothicness of a persisting system is evident where it becomes a repeated process, a curse that the whites hope to kill and bury but keeps reappearing. In stories like ‘Dry September’, Faulkner’s oeuvre shows that racial thinking has “[owned America] body and soul” (9) since its inception. This point can be extended to the white Western experience generally. McLendon’s hate consumes him so much that it causes him to neglect all other aspects of his life. The fear of the other predates the US yet exemplifies the US. It is a disease which has entered the bloodstream and continues to corrupt and turn these white men into African American-hating zombies who are always hungry. McLendon is a descendant of the poor white who believes in a prewritten text about what the African American represents. This inbuilt indoctrination makes McLendon and the other men who join the lynching mob zombies who oppress those weaker to remain strong whilst dehumanising themselves.

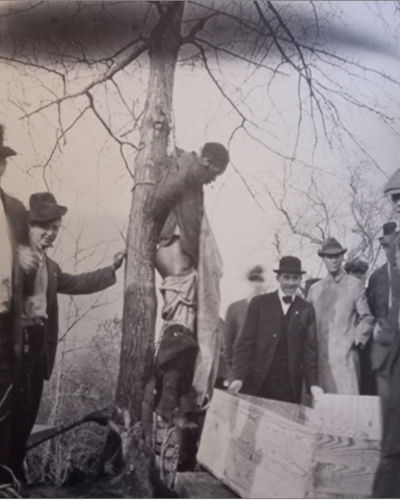

The characters introduced in ‘Dry September’ exemplify the poor and disenfranchised whites. Poor whites are portrayed as being confined in a world of white anxieties that distort their view of blackness to compensate for their continued oppression and the attitudes that have emerged from it. The South contained racist societies, laws and traditions which forbade public interracial relationships. Miscegenation and the history of what miscegenation leads to are unique to American literature in that although African Americans were no longer enslaved people, they remained exploited. Faulkner studies the workings of crowd psychology on individuals and how it drives them to participate in horrible events. Faulkner’s portrayals of lynch mobs, particularly his portrayal of the individuals who become a part of them, challenge the often-cited viewpoint about individuals not being responsible for their behaviour in a crowd. The most disturbing and explicit evidence for this is the celebratory nature of the process of lynching and its aftermath in the popular pastime of commemorating a lynching with photographs and postcards of people posing alongside the dead body of the lynch victim with glee, as can be seen from the image below (see Figure 1):

This savouring of the event contradicts the aim of carrying out a civic duty. Once it is over, the crowd disperses, and there is an enjoyment and a conscious wish to prolong the humiliation in the practice. As West states: “[unlike] the dominant image of the modern spectator, the crowds at lynching’s were by no means passive or disembodied Voyeurs…spectators did not watch or consume a lynching as much as they witnessed it…with active engagement” (West 2013, 39). The claim to a loss of personal responsibility is a fabrication and just an excuse to save face about the horrible things they do and will continue to do for the sole reason they enjoy it. The reason they enjoy it, however, is due to the projection of white fears and insecurities onto black bodies. This is the excuse for enjoying it.

Considering the research, it is significant to consider the mob as a concept concerning McLendon and the lynch mob he brings together to help him regain his sense of worth and the other men. The anxiety and fear of losing what makes them who they are leads to widespread support for lynching, which explains the figure of the lynch mob. Huge crowds who all come together to reclaim their birthright whilst being able to remain anonymous. Personal responsibility is avoided as they represent the South collectively, not as individuals. In effect, by combining into a mob, they can excuse their behaviour and discard normative ethics by appealing to the group’s needs; by themselves, stepping outside of normative ethical frameworks is difficult, but it is much easier whilst in a group. To understand how this works, we must look deeper into theoretical work based on crowd psychology and what aspects play into how lynch mobs develop and function. Le Bon’s work The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1896), whilst not about lynch mobs, highlights many aspects of their workings. Le Bon highlights how the crowd as a concept changed at the end of the 19th century into something distinct from mob mentalities of previous ages. The closing of the 19th century is “the substitution of the unconscious action of crowds for the conscious activity of individuals is one of the principal characteristics of the present age” (Le Bon 1896, iii). The strength of the crowd lies in the fact that individual responsibility can be discarded if personal responsibility cannot be pinned on a particular individual. Then, the inhibitions of all composed in the lynch mob are absent. The prevalence of extreme violence occurs as a result.

Le Bon describes crowds as “little adapted to reasoning” (Le Bon 1896, xi); crowds are distinct entities acting on impulse. Variations between individuals are lost in crowds, and all come to think alike. Nuance or variation is absent, and a common goal is shared by all embodied within the lynch mob. Le Bon seems to exonerate individuals who make up crowds as someone “no longer conscious of his acts” (Le Bon 1896, 7), that crowds sway and influence people who ordinarily would not commit such acts; therefore, an individual who finds themselves in a crowd cannot be held responsible for the things they do. I agree that this is true sometimes, but many individuals who made up lynch mobs could commit such acts. The lynch mob accommodated their deep hatred and fears onto a more significant and disturbing scale than if they did it alone. Despite this, Le Bon does provide theories for the possibility of crowds influencing people who ordinarily would not be so violent. He draws attention to people who bow down to authority: “a crowd is always ready to revolt…and to bow down…before a strong authority” (Le Bon 1896, 25). The ordinary white male finds themselves in a difficult position, as they have been taught to be suspicious of the African American. However, they have no strong compulsions to go out and murder. When those in power tell them they must act as faithful Southern men by oppressing the African American male, they have little choice but to do it because society tells them it is the right thing. Failure to take part debases their identity and their masculinity.

Like Le Bon, Canetti’s Crowds and Power (1960) defines the crowd as a hive mind composed of individuals who lose their sense of responsibility. He outlines growth as a prominent aspect of crowds, stating that crowds aim to increase their numbers to increase their power: “[o]ne important reason for the rapid growth of the baiting crowd is that [no risk is involved]. There is no risk because the crowd have immense superiority on their side. The victim can do nothing to them” (Canetti 1960, 49). According to Canetti, once this overwhelming power is established, two options can be carried out: “expulsion” and “collective killing” (Canetti 1960, 50). Canetti’s study of collective killing is the option used by lynch mobs, which serves as a ritual that allows all in the crowd to have ‘a share in [the victim’s] death’ (Canetti 1960, 50). Once the ritual has been completed, Canetti outlines that the crowd “disintegrates rapidly” (Canetti 1960, 52). Once the deed is done, individuality seeps back into the crowd, and to avoid the full realisation of what has occurred, the individual must depart to avoid personal responsibility for their actions. Canetti’s theory allows a more profound analysis of how Southern societies at the time of lynching functioned. Canetti portrays crowds as groups that share a common goal and are all equal partners in this goal. The victim of this goal is someone who does not share this sense of equality. White Southern society is one crowd that outlines what is acceptable and normative for the South, which is white.

Neil Smelser’s work on crowd theory in the Theory of Collective Behavior (1962) highlights another critical point to be considered when studying lynching in the Southern context. Smelser outlines diverse types of crowds that appear and formulate in specific settings and times in history: “[although] wild rumors, crazes, panics, riots, and revolutions are surprising, they occur [regularly]. They cluster in time…[in] certain cultural areas; they occur [more frequently] among certain social groupings” (Smelser 1962, 1). That: “[some] form of strain must be present if an episode of collective behavior is to occur. The more severe the strain, moreover, the more likely is such an episode to appear” (Smelser 1962, 48). A significant strain was indeed present in Southern society at this time, and the extreme forms of mob violence, such as lynching, show the strain’s size.

Aspects of crowd psychology are present in ‘Dry September’, where McLendon appeals to the men in the barbershop via their inbuilt Southernness, leading to the impulsiveness of how quickly McLendon can form a mob. Concerning miscegenation, if we consider miscegenation as a means to repress black sexuality and assert white sexuality in how not just McLendon but all the men who take part in the killing of Will take immense pleasure when talking about killing Will for assaulting a white woman, whilst they try to humiliate Hawkshaw by calling him a “niggerlover” (Faulkner 1951, 159) by trying to defend Will, reducing him to the position of a woman for not demonstrating his masculinity and whiteness. They alienate him, and he becomes an outsider. The myth of a sexually threatening black male is a big part of the mob’s mindset, and the white worldview demands that this figure be subdued, or you cease to be a Southerner: “Do you claim that anything excuses a nigger attacking a white woman? Do you mean to tell me you are a white man and you’ll stand for it? You better go back North where you came from. The South dont want your kind here” (Faulkner 1951, 160). This strategy of intimidating others to follow what they know is wrong and against the moral good is widespread. In order to live in your society, you must be accepted into it; if you are not, there is no point fighting back if you are to be ostracised.

These old codes and attitudes prevent the mob from considering any other alternatives. Rumour is enough to murder an African American male when a white female is involved because it challenges the South’s moral codes, depriving the white man of the exclusive right to white women. McLendon uses the occasion to assert his masculine force over the African American man he feels beneath him, a war hero and upholder of the purity of the South. The lynching of Will and the enjoyment the men feel in the build-up is what these Southern men live for. It is a ritual by which they can continue to prove their importance to the South and themselves by murdering African Americans when the opportunity arises to break up the monotony of their lives. McLendon arrives home after the lynching to his house, which is “trim and fresh as a birdcage and almost as small” (Faulkner 1951, 170), a mundane space, not the house that a paragon of Southern purity should be living in. McLendon’s bitterness and inner insecurities soon surface once the excitement of lynching has worn off. He hits his wife and sits down: “[h]e took the pistol from his hip and laid it on the table beside the bed, and sat on the bed…he stood panting. There was no movement, no sound, not even an insect. The dark world seemed to lie stricken beneath the cold moon and the lidless stars” (Faulkner 1951, 171). Here, masculinity and power have been drained from McLendon. Alone at home, he does not have to pretend that the lynching is for the protection of white women. The lynching is for himself as his actual life is filled with powerlessness.

In ‘Dry September’, Faulkner critiques the dominant societal pressures within Southern society, creating people like McLendon who hold prejudices that are always on the verge of sparking into violence. The claim of rape against Will allows McLendon to act out the Southern virtues denied him in his daily life. The joy he gains from the hunt and the murder of Will are pleasing because they sustain his existence and accord him a purpose and identity. His wife’s fear towards him displays the irony of McLendon’s views about chivalry and honour. Southern chivalry is an artificial concept with no basis in reality. It is a means to an end, the end being asserting his white Southern superiority, which is the only thing capable of giving him power and personal fulfilment. It quells his insecurity and powerlessness. He fails to see that he is just a pawn in maintaining the white patriarchy. By viewing Will, and the African American as a whole, as a monster, McLendon becomes a monster. He is corrupted by the curse of the white South in miscegenation, which he shares with the men who join him in the mob. The appeal to 19th-century Southern moral views does not connect with the current Southerner and the socioeconomic position that men like McLendon find themselves in. Racial oppression is all that remains from these old views; as a result, white Southern men hold onto it with murderous dedication.

In the case of Hawkshaw, the story presents the pressures of Southern society from the opposite standpoint of someone who wants to help but is unable to. The story presents the pressures from all sides, which lead to either outright violence or helplessness to stand up for what you believe in or are uncomfortable with. Lynching plays a prominent role in American history and the history of racial tension inherent in white supremacist ideology. Lynching was the public symbol and method to assert and maintain white patriarchal power—a way to oppress African Americans to maintain their enslavement after the emancipation of enslaved people. Tied up with lynching and the purposes it served was the urge to maintain white power to combat deep insecurities and fears that the eradication of prior Southern values and hierarchies would lead to the eradication of the Southern white male itself, that they would lose their identities and cease to be a distinct cultural people, which would be a betrayal of their forefathers and their history.

What is illustrated through an analysis of Faulkner’s ‘Dry September’ is the pressures which went into lynching, from the pressures of Southern society, which put under suspicion anyone who sought to defend African Americans from unfounded accusations. Hawkshaw highlights the challenges facing Southerners who faced extreme societal pressure to conform and not deviate from modes of thinking that stressed white superiority. Whether we sympathise with Hawkshaw depends on how we view the pressures he faces; could he have done more? We want Hawkshaw to do or say more. Hawkshaw wants to do more, but who would take his side? The fact that he voices his disagreements and doubts in the first place is a risky move. He would be alone in his fight against much of the South, and the threat of banishment and mob violence would be upon him if he persisted in his opposition. McLendon illustrates the other side of this pressure. Someone so indoctrinated into these modes of thinking that defending an African American over a white person is a betrayal of the South. This concept of the South means everything to McLendon because it gives his life meaning, which his ordinary existence does not provide.

Lynching for a person like McLendon is a cathartic experience where he can make his stamp on his region. In his view, he is a protector of the South, giving him purpose. McLendon’s enjoyment in leading the mob to chase and kill Will stems from the civic duty he feels he is serving. He is protecting his pure South from the African Americans who aim to corrupt it. No easy answers can be given in a story like ‘Dry September’. It is hard to fathom the pleasure and evident glee the members of the lynch mob feel in the act. McLendon’s behaviour is hard to justify, making the story powerful. Anything can be done with a clear conscience. ‘Dry September’ presents the complications and violence inherent in lynching, the factors that facilitate lynching taking place, and how people become swept up in mob violence, losing all sense of personal responsibility. In ‘Dry September’, no one escapes from the past, and everyone remains rooted in it. Within ‘Dry September’, Faulkner introduces us to characters who serve as prime examples of the impoverished and marginalised white population. These individuals represent a psychological response to the oppression and fear associated with African Americans, manifested as a distorted projection of white anxieties. Applying normative ethics can help reveal why people commit acts that are so reprehensible. By applying normative ethics to a textual example, we can see how history influences the present, as the issues in Faulkner’s story are still alive today. It helps us to see how these behaviours work and to ensure we spot these signs to ensure they are minimised as much as possible.

Normative Ethics

My theoretical model derived from normative ethics clarifies the underlying causes of the persistent hatred and violence we see across contrasting times and cultures. Both the US South in Faulkner and the violence in the UK, despite their differences in method, share a common causation of deprivation and scapegoating alongside the manipulation of people experiencing poverty for political causes. Faulkner’s ‘Dry September’ is firmly grounded in historical reality to underscore the crucial role of literature in outlining the historical issues of society. However, it does not provide a definitive resolution or answer. It merely presents the problem and asks the reader to consider its implications. A substantial part of the critical discourse on this subject should recognise the inherent link between literature’s ability to illuminate societal issues and the extent to which it can achieve actual change. It is important to note that while literature can highlight these issues, it is not a solution. Often, a perception of elitism within the discourse oversimplifies the issue and fails to investigate the underlying causes of hatred. My theoretical framework integrates literature with a historical-psychological methodology to examine violence through the lens of socioeconomic disparities. Using the philosophical model of normative ethics, I advocate for a comprehensive analysis of historical and contemporary instances of hate and violence within their real-world contexts. It is crucial to recognise that the influence and interconnectedness of literature and history are both significant in this context. Literature and philosophical analysis must deal with realities if they ever hope to affect any modicum of change. Poetry and elitism in arts amplify the problem that leads many to become misguided in the first place.

To detail this, I will discuss the issue of binary thinking. To apply normative ethics in our lives, we must delve deeper into our shared humanity and humanise those others wish to keep separate. We must shift our focus from our differences to our shared humanity. Hélène Cixous, in The Newly Born Woman (1986), studies the concept of dichotomies. Cixous posits that the history of humankind is one of obsession with opposition and the tendency to group elements by opposing pairs. Cixous uses many examples, such as day and night, male and female (Cixous 1986, 73). We compare two opposing concepts to find what makes them different. These are ranked hierarchically, with one ranked as superior. This thinking is why humans separate themselves into groups: white vs. black and us vs. them. Violence occurs when people sense difference, which threatens their uniqueness and what separates their light from the other’s dark.

We need to evoke normative ethical principles to avoid binary thinking. Recent research indicates that positive steps are being made, for instance, in Bråten’s work, which delves into the role of the educational system in reducing binary thinking. They propose the implementation of a curriculum titled “worldview education” (Bråten 2022, 326), designed to facilitate the comprehension and formation of worldviews with a specific emphasis on non-binary perspectives (Bråten 2022, 327). This curriculum is paramount as it is a crucial step towards a more inclusive and understanding society that will rectify harmful ideologies. By teaching that everyone is valuable, we can reduce the things that separate us, which normative ethics strives to achieve.

Another piece of research on binary thinking is Bonfá-Araujo et al., who studied “Dichotomous Thinking” (Bonfá-Araujo et al. 2022, 461), which uses binary thinking to understand events. They use two main scales for measuring dichotomous thinking, the main one for my purposes being the “Dichotomous Thinking Inventory (DTI)” (Bonfá-Araujo et al. 2022, 461), a broad assessment of cognitive distortion related to dichotomous thinking. They find that psychologically, members of hate groups have a high correlation of dichotomous thinking with various maladaptive traits, which all lead to aggressive and hateful behaviours (Bonfá-Araujo et al. 2022, 462). This is because dichotomous thinking involves a cognitive simplification of events due to uncertainty, leading to behavioural responses like avoidance (Bonfá-Araujo et al. 2022, 462). This thinking is a vicious cycle because it applies to many of their issues, which leads them to develop these behaviours. The psychological implications for individuals displaying dichotomous thinking are significant, potentially leading to distorted reality perceptions and consequent maladaptive behaviour. This underscores the need for further research and intervention to understand how these conditions may form when individuals perceive limited options for seeking help. Additional studies are required to enhance understanding of how dichotomous thinking intersects with diverse psychological constructs and impacts overall mental health.

Finally, another key strategy to changing our approach to violence and people different from ourselves is to adopt a different perspective, one that transcends our personal circumstances and emotions. Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception (1945) explored the interconnectedness of our experiences, showing that the world is unique for each of us and that our minds and bodies are distinctly ours. This understanding that we can only fully understand ourselves and the world by considering our bodily and subjective experiences (Merleau-Ponty 2012, 101) can be extended to the realisation that we cannot fully comprehend our world without acknowledging the experiences of others. In their study, Bursztyn and Yang examined perception and the dynamics of interpersonal perceptions. Their research identified six primary factors that influence individuals’ perceptions of others. Notably, their findings addressed misperceptions, particularly those termed “Asymmetric” and “In-Group vs Out-Group” perceptions (Bursztyn and Yang 2022, 426). Asymmetric misperception denotes the presence of biased perspectives that disproportionately lean towards one extreme, diverging from the truth (Bursztyn and Yang 2022, 426). Additionally, the study expounded on misperceptions concerning in-group members as juxtaposed with those they attributed to out-group members (Bursztyn and Yang 2022, 427). The concepts above explain the influence of individual perceptions and their results in varied degrees of misconception. For instance, the susceptibility to violence shifts when individuals align themselves with others who share their perspectives but who advocate for a more extreme version. Individuals tend to align themselves with their group, delineated as the in-group, and perceive those in opposition as the out-group, thereby fostering division. These concepts yield invaluable insights into the nature of misconceptions regarding others and their potential impact on attitudes and behaviours.

All this prior research is vital to the message I have conveyed so far; however, it is vital to address objections to my argument and respond to them. There appears to be confusion regarding different types of hate and the level of attention they receive. While we readily condemn racial hatred and racially motivated acts, such as the recent UK riots, numerous other examples are either overlooked or not as strongly denounced. This raises the question of why we differentiate in our responses. It is beyond the scope of this piece to delve into detailed explanations. However, it is undoubtedly because of who the people are, their socioeconomic class, and how they are perceived that people easily dismiss their grievances, no matter how misguided. We should strive to understand why they feel the way they do. It is my view that no one is ever born hateful; we are shaped to be hateful. It is imperative to acknowledge that no individual is devoid of prejudices. Whether conscious or unconscious, these biases are inherent. Assuming a moral high ground based on superior education and condescending attitudes toward others does not warrant perceiving them as merely bigoted individuals. It is essential to recognise that circumstances have contributed to their perspectives, and dismissing them without understanding their difficulties would be unjust. Furthermore, it is crucial to acknowledge that one’s advantage in education and privilege does not sanction you to feel superior to others. It is important to remember that humility and respect are key in these situations. Embracing this lesson is something that some critics and observers would benefit from adopting.

Furthermore, the assessment of riots and violence becomes intricate when considering specific instances, such as black riots, which were instigated by a struggle against societal violence and institutional racism. The persistence of racism and racial violence despite prior efforts necessitates a rethinking of strategies. Resorting to violent means is ineffective. Addressing this enduring challenge requires a thorough exploration of alternative non-violent approaches. Key to this effort is education and eradicating the root causes of hateful ideologies. While prosecuting individuals involved in riots is warranted, it fails to address the fundamental issue of individuals feeling marginalised and excluded based on their identity and origin. This approach may exacerbate the problem, as it impacts the families and children of the prosecuted individuals, potentially perpetuating a cycle of discontent within communities. A change in approach is imperative, as violence and recent anti-hate initiatives have proven ineffective. Race riots persist, necessitating an immediate and different course of action.

Conclusion

This article provides an in-depth examination of moral limitations and constraints and their relevance to instances of crowd violence. Utilising the philosophical model of normative ethics, it raised fundamental queries regarding the justification of violence and the motivations behind individuals who perpetrate acts of aggression and hatred. This perspective was exemplified by a historical consideration of violence, for instance, in The Prince, and how it has consistently presented itself unsuccessfully and propagated harmful perspectives and ideologies which have carried down to our current day. Through a textual analysis of ‘Dry September’ through the lens of normative ethics, I outlined the usefulness of literature in highlighting societal issues but that it could not solve them. To solve the issue, I moved on to the concept of binary thinking and the current research into eradicating binary thinking to achieve more equitable societies. Finally, I looked into ways to help those who hold hateful views see the errors in resorting to violence to aid their issues.

This piece has unequivocally stated that violence is never justifiable, irrespective of the underlying rationale. Through the lens of normative ethics, the article underscores the potential of literature to interpret societal issues while emphasising that literature highlights rather than outright resolves these challenges. Critiques are directed towards scholars who, despite adopting the appropriate moral vantage point, do not attempt to comprehend the perspectives of the subjects under study. This deficiency fails to address the root causes of animosity from the aggressor’s perspective, who acts from a sense of victimhood. The article advocates for a theoretical framework that integrates literature with historical and psychological methodologies to analyse violence within the context of socioeconomic disparities. It stresses the importance of situating historical and contemporary instances of hate and violence within the confines of real-world contexts to facilitate a deeper understanding of societal issues, underscoring the interconnectedness of literature and history in effectively addressing and resolving these issues.

Reference List

Allen, James. Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America. New Mexico: Twin Palms Publishers, 2000.

Bråten, Oddrun. M. H. “Non-binary Worldviews in Education.” British Journal of Religious Education 44, no. 3 (2022): 325-335. doi: 10.1080/01416200.2021.1901653.

Bonfá-Araujo, Bruno, Atsushi Oshio, and Nelson Hauck-Filho. “Seeing Things in Black-and-White: A Scoping Review on Dichotomous Thinking Style.” Japanese Psychological Research 64, no. 4 (2022): 461–472. doi: 10.1111/jpr.12328.

Bursztyn, Leonardo, and David Y. Yang. “Misperceptions About Others.” Annual Review of Economics 14, (2022): 425-452. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-051520-023322.

Chouraqui, Frank. “The Duty of Violence.” Human Studies 46, (2023): 21–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-021-09611-5.

Cixous, Hélène. The Newly Born Woman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Godden, Richard. “William Faulkner, “Barn Burning” and the Second Reconstruction.” Irish Journal of American Studies 4, (1995): 23–48. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30003329.

Jahnke, Sara, Katharina Abad Borger, and Andreas Beelmann. “Predictors of Political Violence Outcomes among Young People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Political Psychology 43, no. 1 (2022): 111-129. doi: 10.1111/pops.12743.

Kagan, Shelly. Normative Ethics. Oxford: Westview Press, 1998.

Lawrence, Stefan, and Kevin Hylton. “Critical Race Theory, Methodology, and Semiotics: The Analytical Utility of a “Race” Conscious Approach for Visual Qualitative Research” Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies 22, no. 3 (2022): 255–265. doi: org/10.1177/15327086221081829.

Machiavelli, Niccolo, and Peter Bondanella. The Prince. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Oxen: Routledge, 2012.

Petteway, Ryan J. “On Epidemiology as Racial-capitalist (Re)colonization and Epistemic Violence.” Critical Public Health 33, no. 1 (2023): 5-12. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2022.2107486.

Taylor, Rebecca M. “Methodological Reflections on Normative Case Studies: What They Are and Why We Need Better Quality Criteria to Inform Their Use.” Educational Theory 74, no. 3 (2024): 301-311. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12555.

Tongeren, Paul Van. “Language and Violence,” in Violence in Extreme Conditions Ethical Challenges in Military Practice, ed. by Eric-Hans Kramer, and Tine Molendijk, 17-27. Cham: Springer, 2023.

West, Benjamin S. Crowd Violence in American Modernist Fiction. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2013.

Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. Southern Honor, Ethics and Behavior in the Old South. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.